Book Post

Reading and Writing in India By Hemant Sareen

12 November 2011

05 September 2008

Manto with a Funny Bone

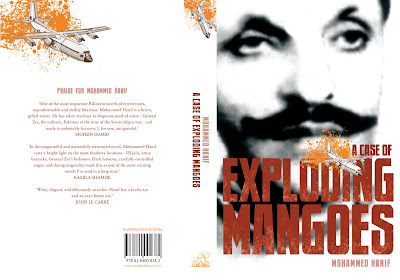

Irreverent, hip, assured. Mohammed Hanif belongs to the new breed of Pakistani writers who herald the birth of a bold, new Pakistan -- only if, inshallah, the army and the mullahs will let it come into being. Hanif, the BBC Urdu Service head who was once a Pilot Officer in the Pakistani Air Force Academy, is the latest entrant in the fast-lengthening list of accomplished young Pakistani writers like Kamila Shamsie, Nadeem Aslam, and Mohsin Hamid, who display consummate skill combined with Sadat Hasan Manto’s hunger to break taboos. Hanif's first book, The Case of Exploding Mangoes, has attracted much attention for its brave, spirited, hilarious look at Pakistan's past. A review in The New York Times even compares it to Joseph Heller's black-humour classic Catch-22. Hemant Sareen, in an email exchange with Hanif, discovers that the suave, cool, wickedly funny voice of the narrator in the book wasn't a put-on act.

Hemant Sareen: How has your book been received in Pakistan?

Mohammed Hanif: Great so far. Brilliant reviews. Wall-to-wall coverage in print and electronic media. And some really sweet emails from random readers.

HS: You must have stumbled upon state secrets to absolve the Bhuttos, the CIA, the Israelis, the Soviets, and the Afghans, not to mention the Indians, all of whom wanted Zia dead?

MH: I didn’t notice that I had absolved anyone. That wasn’t the purpose. I was trying to write a murder mystery with some jokes.

HS: And you have implicated one General (Akhtar, Director ISI) and a Major (Kiyani) from the Army, and the ISI? The book is not just an entertaining historical thriller, it is naming names of real people?

MH: Again, I don’t think I have implicated anyone. You need names for your characters. And Kiyani is a very common last name in Punjab. And as a novelist I think I can name as many names as the plot demands.

HS: You actually suggest that the absolutely powerful, deeply hierarchical, totally unaccountable army-ISI complex was the main culprit.

MH: I do not suggest any such thing. There are some great books out there about the Pakistan army and I think anyone looking for an insight into this complex should read them. My novel will only misguide them.

HS: You were an insider; you were training to be a pilot in the Pakistan Air Force. Did you complete your training? When and why did you quit?

MH: Hardly an insider. I was in my late teens and one of thousands marching up and down the parade squares with an occasional flying lesson. I left because it was quite boring.

HS: What did you learn from that experience? When and how did the experience turn into political convictions, if at all it did?

MH: Sadly, I haven’t been able to turn any of those experiences into any political conviction. I learnt that one should wake up really early, go for long runs, keep one’s belt tight, shine one’s shoes properly, clean my cupboard every week etc. Good lessons all, but I am too lazy to make any use of them in my current life.

HS: You allude repeatedly to the Pakistani army’s self-delusional existence. Does it really believe it is being useful to the country, and that it is popular? One would have imagined over the years it might have been cured of the delusion?

MH: The Pakistan army is not the only army in the world guilty of this delusion. Ask any colonel from the US army or even your Indian army and you’ll find out what they think of civilians like me and you.

HS: Your Zia reads like a Hamlet who comes into knowledge, but late. Was it a literary requirement to humanise the “cruellest of modern tyrants” or do you really think, no harm done, maybe he would have listened to his Koran or the inner voice, and perhaps withdrawn, reformed?

MH: I think you are reading too much into a little plot twist. I don’t think he is redeemed as a character. And as we all know, dictators in our region don’t reform and never withdraw.

HS: Was he, maybe, as much a victim as he was an agency of evil? Was the Islamisation of the army and the society at large that he effected an act of piety and a foreign policy strategy -- and not a tactic to consolidate and retain power?

MH: I don’t think piety had anything to do with it. It was just old fashioned greed for power.

HS: Is there a new clarity in Pakistan about contemporary history? Have people become smart enough to not let another Zia happen?

MH: I hope they have. Millions have marched against Musharraf on the streets of Pakistan during the last one year. And they have forced Musharraf to hold half decent elections, to take off his uniform. I think civil society in Pakistan is definitely on the rise.

HS: Are the Police State elements too deeply entrenched to be uprooted completely?

MH: It’ll be a long struggle.

HS: One of the processes you show in your book is the brutalisation to which the elite of Pakistani society subject their young, hip, secular, modern offspring, which turns them into cynical hate-mongers who abuse religion and power to remain on top of the heap in society.

MH: The elite of Pakistan actually send their offspring to Ivy League colleges, where they get a very expensive education, learn new ways of making money, and make their families proud and richer in the process. Army careers, both in India and Pakistan, are for lower middle classes only, or the academically challenged.

HS: This also suggests that the coups and political upheavals in the country are a way to bring the balance of power back in favour of the elite, who are complicit in their orchestration. Which is why the coups in Pakistan tend to be bloodless -- the feudal elite have only subjects and no competitors?

MS: You are absolutely right but as I said earlier this seems to be changing now. We have a very thriving media, a very determined lawyers’ movement and lots of hardworking rights groups trying to change things.

HS: Is the book a vehicle of your political convictions or are you just trying to be an agent provocateur?

MH: I am a journalist who is dabbling into fiction and hoping to do more of this in future.

HS: What kind of research/investigation did you follow while writing, if you did, or is the book the sum total of impressions and hearsay?

MH: Mostly impressions, recycled rumours. My research involved watching reruns of MASH.

HS: Where were you when you heard about Zia's death? I remember, I was in my late teens and had a personal celebration being in a very apolitical place -- an ashram.

MH: I was also in a very apolitical place, an officers’ mess. We were drinking beer in our rooms. We were shocked and sad so we switched to whisky.

HS: Is Pakistan deciding that the kind of Islam that has gained currency since Zia is not its cup of tea after all? That it’s time to go back to the traditional South Asian Sufi-tinged, gentler, less dogmatic, suppler kind of Islam?

MH: I don’t think anybody is going back to traditional Sufism. There is a very vocal minority that is religious and they are joined by some new converts. Most people are struggling with rising food and fuel prices and really have no time to worry about religion.

HS: Has an increasingly liberal and permissive India (at least in the media and the films) denied Pakistan a familiar model worth emulating -- one that could balance tradition, religion and modernity? The example that comes to the mind is a group of middle-class Pakistani women visiting India, complaining that they find it harder and harder to relate Bollywood because of the western dresses actresses wear in the movies?

MH: Bollywood fashion trends? I think you haven’t been following Bollywood lately. A lot of Pakistani women wear western dresses, you can see them everywhere. Pakistan also has a very vibrant fashion industry. Bollywood is always trying to find new ways of introducing the skimpiest clothes for their women. I don’t think real life women in India and Pakistan have that approach. I was quite surprised about the furore over cheerleaders recently. Obviously people objecting to it have not been to a cinema lately.

HS: You have an MFA from the University of East Anglia. Who was your teacher? Who were your classmates? What makes a young man training to be fighter pilot land in a writing course?

MH: I have been a journalist for a decade and a half, and I wanted some time off to write. That’s how I ended up at UEA. I had some brilliant teachers there. Patricia Duncker, who is the author of Hallucinating Foccoult and many other brilliant novels. Then we had Andrew Cowan and Michel Roberts. Also Richard Holmes taught me a life writing course which was great. Had lots of people in my class: Ann, Vicky, Laura, Emily, Ralph. All great readers and good company at the college bar.

HS: What is your ideal of writing? Who is your favourite author?

MH: I think, trying to find out what you don’t know. You sit with a blank page and you have a very vague idea about what’s going to happen. That really is a delicious feeling when you find out what is going to happen next. My favourite author is Truman Capote. Current favourite author Mirza Athar Baig, who wrote Ghulam Bagh.

HS: A writing school degree on the back cover blurb usually means a serious, literary, personal, well-crafted book. You’ve come out with a lean but breezy historical thriller.

MH: Is that a compliment or a complaint?

HS: The book reads like a movie at times -- the plotting, the pacing, the cuts in and out, the dialogue, and the set pieces (eg Zia’s night out on his bicycle). Are you still into your other passion, cinema?

MH: I have written a movie and a half. Passion is a bit of an overstatement, though. Occasionally I get passionate about theatre. I have written two-and-a-half plays. It’s the best feeling; sitting in the audience, watching people react to your words. I am in the middle of writing a play called The Dictator’s Wife. I’ll be sitting in the audience.

HS: I thought the book, because it machetes away the complexities of the times and around the event, to be guilty of low ambition. Did you ever consider a more monumental, dense, complex, solid book? Or did you plan it that way, but then received a call from Islamabad to knock it off, so settled for a book that moves from one one-liner to the next?

MH: I have written a very monumental, very dense book, and I think the most complex book I have ever written. Sorry you don’t agree. Will try harder next time. I am also glad you recognise that I lack ambition. The only calls I get from Islamabad are from our BBC bureau and trust me they never say, ‘Finish that bloody novel!’

HS: While writing the book, you must have been thinking up Pakistani-flavoured witticisms all the time? You must have been some company to keep in a pub?

MH: Pubs are for writing. Only bores talk in pubs.

HS: What’s your view on how Pakistani writing is coming up and the direction it is taking?

MH: The best Pakistani writing I recently read was a novel called Ghulam Bagh. A philosophical, archaeological thriller. Everybody should read it. I think that’s the direction Pakistani writing should take.

HS: Does being a part of the BBC make you an agent of the West in Pakistan, like it made foreign journalists and their Indian colleagues suspect in Indira Gandhi’s time?

MH: I wasn’t there in Indira’s time. People are generally suspicious of journalists, local or foreign. And I think they should be.

HS: The BBC's maternalism looked a bit out of place in the free-market culture fast becoming the norm in the developing world. Now, what with global warming and food crises, it seems relevant again?

MH: BBC bosses would love this.

HS: Is Pakistani private, independent media an established fact now? Can this advance ever be reversed?

MH: No.

HS: Is there another book on the hard disk?

MH: Only on notebooks.

04 September 2008

The Tazurba of Amitav Ghosh

Photograph © Hemant Sareen

Amitav Ghosh, with his mop of since-ages white hair and a pleasingly contrasting dusky skin, stands welcoming you in his tenth floor suite in a five-star Delhi hotel looking like a weightier, intellectual, grown-up, oriental Tintin. There are signs of the whirl of book launch-related activity---boxes full of copies of his latest book, presumably meant to be given away to old friends from Ghosh’s long stay in Delhi, are strewn on the floor. You realise, here is a man who perfectly embodies the image the middle class India has of an Indian Writer in English---a material and creative success; someone with a universality that comes from being a perfect mix of Indian-ness and westernisation, a man as comforatble in a Harvard lecture room as he is in a boat afloat in the Sundarbans; and a nerd with a great presence, equally at home at his desk as he is at a book-launch party. As he engages the photographer in easy conversation about an old Stephanian connection they have both discovered, you feel the ice is broken. Nope. Almost rendered inarticulate by Ghosh’s combativeness, Hemant Sareen discovers that the author of nine books that have constantly countered the West-centric world view, Amitav Ghosh is not someone to whom one mentions ambivalence and the Empire in the same sentence.

Hemant Sareen: Sea of Poppies is an indictment of colonialism but it was surprising to find the heroes and the villains so neatly separated into good and bad guys. Also, the fact that all your British characters are shown as snarling rascals.

Amitav Ghosh: Are you sure you read my book? My book is about marginal people and all of them are deeply flawed. The central character Deeti has murdered her own mother in law. They are all either criminals or on some side of criminality. Another character is a forger. And the single most genuinely evil character in the book is Bhairon Singh. So what it really show when someone asks me that question is that they cannot believe that an Englishman can be bad. I should only bring out the badness in the Indians and no one else, is that what you are saying ? It wrong to bring out the badness of Englishman, is that what you are saying?

HS: Not really!

AG: But that seems to be the sound of it! It’s interesting to me that you are reading it [the book] that way because it seems you have an agenda!

HS: Having read your other books, especially the first two, The Circle of Reason and The Shadow Lines, the Empire as something so unambiguously evil as it is portrayed in Sea of Poppies doesn’t cross the mind.

AG: The Shadow Lines is not about drug smugglers or slave traders. How many gentle Arab slave traders have you read about? And that is really a racist thing because many of them [the Arab slave traders] were really sweet people. Very kind, very gentle. Similarly, how many good-natured Colombian drug traders have you read about? And I am sure that’s a terrible distortion [about depicting Colombian drug lords as hardened trigger-happy criminals] because they have families, they are nice to their children.

HS: If the British were so plainly evil, you have not painted their victims in primary colours, they do not really act like victims. In fact they are shown as much victims as beneficiaries of the changes drug trade brought in the circumstances? Caste system is suddenly in flux, religious taboos are broken, societal oppression is replaced by indenture, but all in all the indentured labourers are looking forward to the journey across kala pani, there is even romance on the ship hardly out of Hooghly waters?

AG: It doesn’t interest me to write about the victims of the Empire. What interests me is people who make their way in a very difficult world. That’s what my Indian characters do [in Sea of Poppies], that’s what my French, American and English characters do. Some ways they are all participants in the evil of the circumstances they live in.

HS: You wrote in your essay The Ghosts of Mrs Gandhi (1995): It is when we thin of the world the aesthetic of indifference might bring into being that we recognise the urgency of remembering the stories we have not written. What was the urgency you felt to write about the indentured labourers, the Jahaj-bhais and -baihans?

AG: When I started thinking about this book especially when I travelled to Mauritius and met people there, one of the things that really struck me was this aspect of their remembering -- their ancestors, relationships --as they crossed the waters and came together, and they often spoke of [these fellow travellers-indentured labourers] as Jahaj-bhais. That was a beautiful thing and I would think about it, and write about it.

HS: And, of course, the book continues with your abiding writerly concern of retrieving from extinction histories on the verge of being forgotten, especially the histories of marginal people?

AG: The thing about dealing with marginal people is that marginal people often have to do terrible things just to stay alive. And it’s never easy for them to survive in the circumstances and the world they live in. So many of the indentured labourers whose portraits are painted are painted in Sea of Poppies are people who in some ways emerging from poverty become warped by it.

I think the 19th century was incredibly hard, incredibly bitter, and it’s strange that people have such a toffee-coated notion of what life was like in the 19th century. It was an incredibly ferocious, violent life. In fact, if I were to reproduce the real violence of the slave ship and what slave, opium traders did, the actual reality of what they were doing , you’d probably not believe it because, of course, you actually think all Englishmen were nice, gentle school teachers. [Laughs]

HS: I am not going to ask you what the next book in the Ibis trilogy is going to end, but tell me why a trilogy?

AG: Hmm, because I want to have the time and space to explore this [the above] at some length.

HS: Is it a theme or the story that is driving the trilogy?

AG: What I am going to do is just follow the lives and destinies of these characters.

HS: The first book reads like ‘to be continued’, ‘part one’. Not so much a triptych as a book in three volumes this Ibis trilogy?

AG: It could be more, four, five, or, even more volumes. I don’t know. I’m thinking of three.

HS: You regard the novel as a national narrative. It seems now that you are trying to consolidate your oeuvre, project your pet writerly concerns on a larger scale.

AG: It is interesting what you said there. I don’t regard the novel as a national narrative at all. A large and a national narrative are different things. [The novel to me] is not national in the sense of relating to contemporary India. Sea of Poppies is a non-national narrative in the sense that it is about people who are leaving India behind.

HS: You have a problem with the concept of nation. You regard its artificiality as antithetical to identity’s organic-ness. Do you have an alternative to it in the Subcontinental context (something like a European Union)?

AG: My feelings about this are twofold. One is that we should be very keenly aware when you say artificial. One thing we do have to understand is that the nature of the relationships with our neighbours is civilisational, it is linguistic. These are deep and enduring relationships. And we have to remember that we can’t make them seem as though they were ancient because they are not. They are new.

At the same time you know the nation state as such, artificial or not, is a very important institution. It is an institution because it provides a forum in which people can negotiate their differences within which they can also implement policy. So, the nation state in my view serves a very important purpose and I don’t in any way discount or devalue the nation because I have actually seen what happens when a nation state is disappears. In fact, what you then get is warlordism. And the nation state is greatly preferable to that -- although within our nation sate we do have entire areas that are run by warlords. But even in this day and age, we have to consider ourselves very fortunate that we have a functioning nation state and it functions in a democratic way. These are great achievements and in no way to be discounted.

HS: The Novel or fiction, you have often said, is preferable to both history and anthropology, the subjects that you pursue in your academic life, because the novel can accommodate both these disciplines and much more?

AG: I do. I think other than history and ethnography, the novel can include a lot of other things that other genera cannot encompass, like food, climate, air. What is really exciting about the novel is its expansiveness. Its ability to take in the whole world and hold a mirror to the world.

HS: You told the BBC once that you feel uncomfortable writing in an adopted language. ‘I do battle with my self,’ you said. But reading something like The Shadow Lines, in which the language is supple, organic, and seems totally unforced, that you’d believe a native speaker was writing it. Even now the new experiment in language you try in Sea of Poppies, gives an impression of a writer fully at ease with the language. You have tried to present the times and the characters through language. There is the Anglo-Indian patois; there is Laskari, the language lascars, the Indian or South-East Asian sailors of the time spoke, usually translating the English Maritime jargon into vernacular; there is babu English, vernacular directly translated into English including the syntax. And then there is Bhojpuri.

AG: I love those interstitial languages. Just in general though, why do we think of any writer’s relationship with the language as something that’s comfortable? What’s good about being comfortable with the language? Any writer’s relationship with the language should be difficult, not comfortable. That is exactly from where writing emerges. You are pushing yourself against something. You are meeting resistance, and you meet the resistance within yourself. So, for me the fact of being in a difficult relationship with the language is much more interesting than being in an easy relationship with the language. Language isn’t like a hot water bath that you just to lie down in and forget about yourself. Language should be something to be struggling against. I think to have a counter-statutory, difficult relationship with the language has at least for me been a highly productive thing. It’s a very good thing. It’s what my writing comes from.

Also, my writing comes from a sense of multilinguality---from the multilinguality of India. An Englishman, an American, a Thai, a Frenchman---they don’t know lots of other languages because their reality can be lived in one language. Our Indian reality cannot be lived like that. It cannot be experienced like that. It follows that the books we write will reflect that. In my case, my father’s family settled in Chapra in 1856 --- 150 years ago. In my father’s family they always spoke in Bhojpuri to each other. And I so enjoyed listening to it. It is a very beautiful language. I remember most of my Bhojpuri through music---through kajris, hooris, dadra, and so on, such beautiful forms of music.

HS: Your idea of the novel is very historical in the sense that in early novel, like Cervantes’ Don Quixote, travel provided the plot, the setting, character development. Why did travel become such an important motif in your works?

AG: As you say, Cervantes, but also because I travelled a lot. My family, as I told you, travelled from Bengal to Chapra and that was not a one-way journey---they had to go back to Bengal to get married---so it was a continuous [to and fro]. And I think this is an interesting thing about India, Indian migrants continuously travel [within India] and not just one way. Travel helps me organise a story. It helps me tell a story.

HS: You refused the Commonwealth Writers Prize in 2001. Has anything in the world changed or your own views to reconsider your views of the Commonwealth?

AG: Absolutely not! I think, if anything, the world has gone in the wrong direction. When I rejected the prize, it was before the Iraq war and I think what you are really seeing is the return of colonialism. a kind of Anglo-American imperialism. And that is the whole problem with the Commonwealth. My rejection of it is based on the idea that the Commonwealth is a euphemism. It’s a whitewashing of the past. The Commonwealth historically meant white settler colonies. It was only after the 1940s that they began to include non-white colonies in it. Look at the Commonwealth’s history, it was a hideous thing.

HS: You have qualms about globalisation?

AG: I have qualms about the globalisation of Capital to the exclusion of the globalisation of Labour. That’s really the problem. What it all adds up to, what the contemporary globalisation has become is a way of always seeking cheaper and cheaper labour. Whereas the idea of globalisation to me is that of cultural contact, of cultural exchanges between people and civilisations. That to me is the most wonderful thing that can happen to human beings. And it has happened, there is nothing new about it. It goes back to millennia. So, that is something I completely embrace and celebrate that aspect of interchange. I wrote In An Antique Land which was about pre-colonial globalisation. Globalisation under the control of a few dominant nations is the globalisation of slavery and indenture. That’s not the globalisation I would want.

HS: Interconnected world easily lends itself to romanticism. Even in Sea of Poppies, you depict the 19th century globalisation as extremely unfair and exploitative, but you also show how it allowed Indians to cross the kala pani, break crippling religious taboos, shake up the age-old caste system a bit. Inequity is part of globalisation just as it is of real life. There is both good and bad to it.

AG: That you can say about anything. Even about Nadir Shah, presumably. [Laughs]. What can one say about that?

Before the Europeans entered the Indian Ocean, the sort of exchanges that happened between people were not necessarily iniquitous. There was a certain amount of inequity naturally as there always is in human society, but the bases of the terms of the trade were not iniquitous necessarily.

HS: You write in an essay about V.S. Naipaul’s role in turning you into a writer. There were other Indian writers around and there was Salman Rushdie. Was he an inspiration?

AG: Rushdie is a wonderful writer, but he wasn’t writing when I was in my formative years. When I was in school and college, it is very hard to explain to young Indians today that, there were so few people writing about experiences like ours. So we always sought them out. I read every word I could find of Naipaul. I hunted him out. And not just Naipaul, but also his brother Shiva Naipaul. Also, Sam Selvon who is another major Caribbean writers, and one of the great inspirations in my life, James Baldwin, the great Black American writer. But the writers who were available to us in those days like Nayantara Sehgal, Anita Desai (whose work was very important to us in those days, and it was quite different from what it is now), and others like Aubrey Menon, who are forgotten, I don’t know why. All these writers were great inspirations to us because there was nobody else. We had to read them.

Today, when I walk into my nieces’ or my nephews’ rooms, their bookshelves are filled with writers from the Subcontinent. I feel so happy for them because it’s a wonderful thing that they can see their experiences reflected in the works around them. I think this is one of the greatest things that has happened in these last many years. It just wasn’t there for us.

HS: The direct, sparse language of The Shadow Lines that sought a direct connection with the reader was surprising for the fact that the book was written when magical realism with its lingual frippery was in vogue--- you too had flirted with it in The Circle of Reason just two years before Shadow. Where did that confidence come to buck the trend?

AG: Style is an interesting issue because it pertains to each book. In the process of writing it the style, that is appropriate to the book, emerges. So, that was what happened with The Shadow Lines. It was different for The Calcutta Chromosomes.

It comes out with the process of writing. There is a very good word ‘tazurba’ which is both experiment and experience. In that sense this is what it is---from ‘tazurba’ of the writer the form emerges.

18 July 2008

Through Eastern Eyes

Photograph: Hemant Sareen

Photograph: Hemant SareenKUNAL BASU LEADS A DOUBLE LIFE. His day job is as a Reader in marketing at Oxford University, and you can tell the Oxford don in Basu by the rhetorical, interrogatory ‘Okay?’ with which he ends almost every sentence, making sure he is understood. Basu’s other life is as a writer. His three acclaimed novels, The Racists (2006), The Miniaturist (2003), and The Opium Clerk (2001), and his recently released collection of short stories, The Japanese Wife, are somewhat like red herrings in the post-Rushdie canon of Indian writing in English. They buck the trend of post-colonial, often self-confessional, ebulliently nostalgic narratives obsessed with defining India and the self. Basu looks outwards instead, with no inhibitions about who can write about what -- only stories and ideas matter.

That might give the impression that Basu’s inner life is not be complex or knotty enough to write from and about personal experience. Far from it. Hemant Sareen caught up with the author to discover a man with a full-sized kit of contradictions that he carries with élan, never allowing it to bear heavy on his persona of the well-adjusted, successful-as-they-come Indian writer in English.

photographs by Hemant Sareen

Hemant Sareen: So far you have written novels of ideas, narratives with a historical sweep. Your latest book, The Japanese Wife, is a collection of short stories about East-West encounters. You seem to be working with themes, or perhaps a theme that is trying to explore the East-West equation?

Kunal Basu: I do not work with themes, I think in terms of stories. These stories are about people, about context, about relationships, and in some stories the context is that of the East’s interaction with the West. If there is one overarching theme that connects all of all my writing, and it is difficult to find such a theme, it is perhaps one of humanism, of compassion -- compassion towards the oppressed in society, towards those who are disadvantaged, be it the opium addicts forced into addiction, or the young woman from the story ‘Long Live Imelda Marcos’, whose life is destroyed because a prospective husband is killed in a riot.

Purely cultural contact or conflict between the East and the West bores me to death. I am not interested in that. I am not interested in people from different cultures meeting and having difficulty of language, customs, manners. Or about NRIs living in the West and having cultural conflicts because their children are dating Caucasians. What I have tried and am interested in, and hopefully these short stories reveal that, is people who meet in unlikely places. Unexpected encounters in unlikely places spark off dreams, memories within them. And it can happen even to the most ordinary among us.

“Purely cultural contact or conflict between the East and the West bores me to death. I am not interested in…NRIs living in the West and having cultural conflicts because their children are dating Caucasians.”

HS: You write very easily about the world beyond India and what your readers would imagine to be your own immediate world as a Bhadralok Bengali man. Where does that outward looking world view come from? Has it anything to do with the communists’ notions of Marxist internationalism, given that your father was one of the founding members of the Communist Party of India (CPI) and later the CPI(M), and you yourself were once a cardholding member of the CPI(M)?

KB: Not simply in terms of politics, but culture as well. I grew up in a house full of books; a bookish house, one might say. My father was a publisher and my mother an author of Bangla fiction. She is still alive, 86 years old, and still very prolific; she published her memoirs a few years ago and a collection of short stories last year.

I grew up with intellectuals, my parents’ friends, all around us -- poets, politicians, filmmakers, theatre actors. In the crucible within which I grew up there was an absence of prejudice of any kind -- race, gender, caste, religion and what have you. The world was open to us. We would read Tagore, but we would also read Tolstoy. We would watch films by famous filmmakers from around the world. Art was a very significant part of our upbringing. We would forever be talking about artistic movements in different parts of the world. So it was an enlightened childhood that gave me the values of humanism, of universality, of not being restricted by prejudice. And I have carried that through my life.

HS: When you became a member of the CPI(M), was it a given that you take up the family’s political affiliation, or was it your own decision?

KB: It was a conscious decision. I was actually into the arts, theatre. I acted on stage in school and later in college; I was also into painting. I was not into writing, though I did write a little here and there. I think my political consciousness took shape at the time the Emergency was declared. I was in the early years of college, and to me it was a huge jolt. For the first time since 1947, we Indians were in a situation when our fundamental liberties were being curbed. I said to myself that as a thinking Indian I needed to oppose it. That took me into the realm of politics. But bear in mind, my political life actually was very brief. In 1978, soon thereafter, I graduated and went abroad to study.

HS: Brief, yes, but you still managed to have MISA [Maintenance of Internal Security Act] files on you?

KB: But who wouldn’t, in the 70s in India, in Bengal, struggling against the Emergency? I was no exception.

HS: From a CPI(M) cardholding member to professor of marketing at Oxford. That’s some transformation. How easy or difficult it is to rationalise these contradictions in your life?

KB: I don’t see it as a contradiction. We aspire to and believe in lots of things at certain points in our lives. They don’t necessarily stay the same 20 years later. Today’s views, even in the Left, about capitalism have changed from the time I was growing up in the 70s. The world is dramatically changed. The Soviet Union no longer exists. China is the most powerful communist country in the world now and uses capitalist methods.

[Also], I realised very soon after 1978, when I went abroad, that I am not really comfortable as an organisational being. That’s not my personality. My personality is that of an individualist who thinks about things, sits down and writes. So here was a clear departure away from organisational politics. At some point as I was growing up in my post-University years, I realised the futility of strong ideological views of any particular orientation. Instead, I became interested far more in how common, ordinary, poor, disadvantaged people in this world can be helped. I became more concerned with methods than the ideologies behind those methods.

“I am not really comfortable as an organisational being. That’s not my personality. My personality is that of an individualist who thinks about things, sits down and writes.”

HS: You are very deeply situated in the West. You are part of an institution, Oxford University, which is the epitome of Western values. From that vantage point, what kinds of changes you have seen in Western views about India and the East over the years in the West?

KB: First of all, the advantage of being an author who is also an individualist is that I do not have to subscribe to the philosophies and views of the institutions I work for. If I work for a large company, it doesn’t mean I have to identify with what the company does and stands for. It is just a way for me to make a living. It is my profession. The advantage of being an academic in any institution in the world, in the East or the West, is that I can be what I am. I can believe in what I believe in and can write what I want to. I don’t have to be located within any particular paradigm. I can choose my paradigm wherever I live.

Views about the East are changing of course; I don’t need to say that. The face of the world is turning towards the East. It is turning because of economic reasons. Those economic changes are causing ripple effects in [international] politics. Asian nations have become important political players. In every domain Asians are making their presence felt. I hope in arts too.

HS: You were talking about the liberty to think, write, and speak in the places where you have lived. That is no longer to be taken for granted in India?

KB: This is a matter of contention. If you as an author or as a person in the arts take a strong position, you will be opposed and criticised wherever you are. I will give you one example. When Racists came out, which is a story about 19th century European racism, the book was extremely widely reviewed, but there were voices that criticised it very sharply saying, ‘Why is he writing about us? Racism is something that has gone and disappeared. Why is he bringing all that up again? Why is he corrupting the minds of young generation with these ideas about race?’ I wanted to write back -- though as an author you never write back to the reviewer -- and say, ‘I wish that was the case. But look at the racism around.’ In 2006, when Racists was published, race riots [had raged] in Birmingham, Sydney, Paris, and New Orleans.

So contentious views would be criticised anywhere in the world. What one hopes is that the kind of criticism or discourse remains civilised. I know of the events and incidents you are alluding to here. In such cases, civil society needs to step in and say: Look, people can have different views that you consider outlandish, but it is important to air these different views.

HS: Do you feel certain expectations, if not pressure, to write a certain kind of novel, say, a more personal book?

KB: I don’t. But I know what you are talking about. The expectations that, you know, he is an Indian, he should write about the ‘hot’ Indian themes such as the Bombay mafia or religious fundamentalism. I don’t pay any attention to that because I have to be very sensitive to the stories that I think about. And if I like my stories, those are the ones I will write, always, regardless of what’s the fashion of the week or what anyone expects. I hope my readers will like what I write. But I will not write and have never thought about writing stories that fit expectations.

HS: You are considered an outsider to the Indian-writing-in-English literary marketplace, a stranger to its hardsell, self-promotional ways. That is a bit strange for a professor of marketing?

KB: Do I want to be commercially successful? Absolutely. Every author wants to. And my books sell pretty well and are popular not only in India but in other parts of the world too. But at the end of the day, I write literary fiction, and you can’t have an eye out for commercialisation of your work. If people like it and it is widely, widely appreciated, I would love that. But I won’t market myself; that’s the job of the agent and the publishers. I need to stay focussed on what I do, and what I do is write fiction. And bear in mind I have written four books in less than seven years! I have to be extremely focussed on my writing.

“At the end of the day, I write literary fiction, and you can’t have an eye out for commercialisation of your work. If people like it and it is widely, widely appreciated, I would love that. But I won’t market myself.”

Labels:

Indian Writing in English,

Kunal Basu,

Penguin

08 May 2008

The Twice Born Indian

Photograph: Hemant Sareen

Photograph: Hemant SareenWhen Manil Suri, a professor of Mathematics at an American University, wrote his first novel The Death of Vishnu (2001) he admits its critical and popular success around the world felt ‘disorienting.’ The internationally bestselling novel, translated into dozens of languages, was a heady mix of the mythical and the modern, about a man named Vishnu dying in an apartment building in the crowded city of Bombay. Initially just a one-off book, it grew into a full-fledged Hindu epic in three parts thanks to his agent who wanted to know if Suri had another book in the offing. Suri, off the cuff, offered to write a trilogy on the patriarchal Trinity of Hinduism Brahma-Vishnu-Shiva not necessarily in that order.

Now, seven years later, Suri has come up with the second book The Age of Shiva, an intimate epic that simultaneously reads as a personal narrative of the coming of age of young girl from being a silly little shadow of her elder daring sister to a woman of independence and the story of India from Independence to a free nation negotiating a torrent of choices, not all of them easy. Hemant Sareen caught up with Manil Suri to talk to the writer and his vision.

Hemant Sareen: The Age of Shiva is part of an allegorical trilogy based on the Hindu Trinity. One expected to read about a character based on Shiva, just like in the first novel of the trilogy The Death of Vishnu actually had a central character named ‘Vishnu’. But instead this is a book written from the point of view of Shiva’s consort Parvati, reflected in the leading character Meera, the daughter of a Punjabi, Daryaganj-based publisher telling her story from a young girl to motherhood. What was the design behind it?

Manil Suri: I actually started writing the book about [Meera’s] son, who was supposed to be Shiva. At some point I said ok, let me write a bit about his mother and have some back story about her. At that point I started reading a lot about Indian history, and it was the first time I enjoyed history -- I always hated history. I got so involved and inspired by it that I said I have to interpret this word ‘Age’ as something to do with India, make this a novel about India.

Before I knew, I had written 200 pages about this woman, and the son still hadn’t been born. I new then, it was really [going to be] about her, rather than the son.

The question then was how to still have it in the context of Shiva. And the way I interpreted it is that Shiva is an ascetic. He’s also a destroyer. But the way I have been told he is a destroyer is that he withdraws from the world and without his participation the Universe winds down. He is most often felt by his absence. When he withdraws from the world, a vacuum is created and people have this intense longing for him. Much like a mother has for her son. In this context it was natural to bring Parvati in. She was the one who actually feels this absence, and what happens in Shiva’s absence.

HS: This is a political novel too.Your Parvati-based character in the book, Meera, also represents India. Early reviews consider the politics of the novel distracting. You said once that before publishing an academic mathematical paper, you comb through the drafts to weed out extra equations. Could you have excised the political equation in the novel?

MS: I approach a novel as something very multilayered. So what is attractive to me is if you can have several interpretations of the novel. So, there you have Shiva and Parvati myth that is going on. Then there is this story of a woman making her way in this male-dominated world. But there is also the maturing of India in the background. After Independence this young country is coming of age just like the female protagonist of the novel. So, to have eliminated the politics would have cut out one whole level of complexity. That I didn’t want to do.

Politics is very much [a part of this novel]: the political maturation of the right wing in particular, is a very important, [as was] the experimentation with Emergency. [But] all these things are in the background. They are not the primary focus. The primary focus is still the woman, the family story. Like all those authorial ambitions are best layered underneath.

HS: What does it take for a man to write from inside a woman's mind?

MS: Here’s what I did. When I knew I was going to write about this woman, before [starting] the novel I read a lot about women who had given birth, the idea of breastfeeding. There are some web sites for example where women have been sharing their experiences, like the kind of flush that they feel when they are breastfeeding an infant. I read some texts like Of A Woman Born, a classic feminine text by Adrienne Cecile Rich.

At some point though the research had to stop. And then I just said to myself, ok, now I have to feel what it means to be a woman. I had filled my head with facts, let me try to feel [now]. It was only after allowing myself to ‘feel’ for almost two months that I actually sat down and wrote the first two pages. After that it was still a matter of feeling -- and intellectualising too -- but really feeling, trying to enter Meera’s mind, and taking small steps, looking at the world through a woman's eyes. lt was a very long process. It took seven years to write this novel. It was also scary, I wasn't showing it to anyone. I wasn't showing it to women and asking 'Is this correct?' I had only my own intuition to guide me.

One of the things was this [relationship] between the mother and son that I explore. It has been really talked about a lot by Freud, the Oedipal Theory and so on, but it was always from the male point of view. I looked all over but couldn’t find anything from the female point of view.

HS: Like Salman Rushdie you seem to reject belief in favour of myth while you embrace your Indianness. But compared to Rushdie, your take on Indian myths is much more earnest?

MS: I am sure all those things are correct. One thing I must point out even though it doesn't not address your question is that whenever I read an author like Rushdie or Naipual there is always a red light that goes on in my head saying, ok, this is someone very famous, you have to go perpendicular to it. You can’t do the same thing. So there is always this kind of censorship that goes on anytime I find myself [drawn towards them]. Like in the first novel, was tempted to dabble with magic realism. But I said no, that’s Rushdie, let’s stay away from that. Especially for younger authors, they seem larger-than-life icons, that we have to kind of stay away from them. So when you compare me to them, I get nervous.

HS: But isn’t it a process of acculturation -- you go abroad, you start thinking about your Indianness, consolidating it? But it so happens that belief or religion is easily eschewed? Culture, mythology, no problems.

MS: Everything you say about consolidating my Indianness is correct. Just as I was inspired by history in Shiva, in Vishnu I was inspired by religion. I am an agnostic, but I read the Bhagwad Gita and I found myself inspired by it. And that is what I was really trying to bring out -- just the philosophical underpinnings of Hinduism. Which can be interpreted in different ways. You don’t have to subscribe to the whole religious aspect of it. You can just take out various spiritual things.

HS: The microcosms that you have created are too true to be imagined. Where do they come from?

MS: The first one was inspired by my own situation. When I grew up it was as a paying guest in one room of a large flat in Bombay. There was actually a kitchen, and toilet that everyone shared. Also, though this was not in the novel, we were the only Hindu family and there were three Muslim families in the rest of the flat. So it was a very fraught situation. Even though it turned out that most of the fights we had were not about religion but space. When you are all packed together its space that counts not culture.

The Age of Shiva is set in Delhi where I hadn’t spent much time in. I never experienced a joint family. And I didn’t know anyone in the family who did. So that was sort of imagined. It actually came about when in my university UMBC [University of Maryland, Baltimore County], the president has taken a real interest in what I ave been doing. So one day he just asked me, ‘You know these joint families in India stay in one big room. When a couple gets married how do they have sex?’ And that is what started me thinking well how am I going to engineer this [make couple have sex in a shared room in a joint family]. The setting is Nizamuddin where my uncle used to be a station master. So I know that area and I know a little bit about that. But every thing else is made up.

HS: Two books out of the trilogy behind you, do you have a sense of what you are aiming at in the trilogy?

MS: Yes. And it has been a process of evolution because it was really about mythology but now its become about India. Where the first book was a snapshot of India in contemporary times, the ‘80s and the ‘90s, this book is the evolution of India from the Independence to how it got to the [present] point. The next book is going to be a prediction of what is going to happen in the future, so propel it [India] into the future.

HS: The novel as a narrative of the nation, novels with scope and breadth, something like the 900-page long Sacred Games by Vikram Chandra and now your The Age of Shiva, these seem to be coming more from the Indian writers living in the West. How important is the West for an Indian writer?

MS: I haven’t finished reading Vikram Chandra’s book, but I know it is a long epic. Certainly, Salman Rushdie’s books like Midnight’s Children are very encompassing of the whole picture of India, maybe that is what you are alluding to.

When you go away [from India] you have time to reflect and consolidate. You start seeing India as a whole. I have been very fortunate that I come back three times a year. So I get to see both aspects. I don’t know if it is a very Western phenomenon, there are many authors who are living in the West who have a much more intimate views and picturisations of India. But surely you can pick up some Indian authors [in India] who have an epic view of India? I don’t know.

HS: Not any contemporary writer.

MS: Then there is a mathematical theorem there then, almost!

HS: Apart from making one rethink one’s Indianness and the material support in terms of literary agents, editors, publishers, advances, not to mention markets, do you think the West is our constant interlocutor? An easy audience because you must always begin from the beginning while you explain yourself to the West?

MS: It is hard to say. Like for the first novel, even though I was living in the West, I don’t think I had any particular audience in my mind just because I had not yet been published. So I wasn’t thinking of advances and publishing. With this novel, I think I had to make a very conscious effort to keep shutting out my audience. Because it is so easy, since this novel is so steeped in culture and history that a lot of the references will not be fully grasped by the West. And I am quite resigned to that. Even the character of Meera, I found that the few western readers who read Shiva have been much less sympathetic to her than people in India have.

So that is the kind of danger you [under]take for a novel to succeed. I have seen many [Indian] novels where there is an actual pandering to the West like ‘samosa’ with an asterisk and then at the bottom it says ‘a pastry filled with peas and potatoes.’ That is the kind of thing one has to avoid. I will say that what you are saying is true at the subconscious level. But consciously, I try not to think which audience I am writing for.

HS: You have attended writing workshops by Jane Bradley, Vikram Chandra, and Michael Cunnigham. What was the most useful piece of advice you picked up from them?

MS: The best piece of advice was from Michael Cunnigham who said, based on the first three chapters of The Death of Vishnu, ‘You are a writer,’ and he was the first to call me a ‘writer.’ He said something like, ‘I don’t know what advice to give you except this that you have to finish this [Vishnu] at every cost.’ That was the best piece of advice.

HS: You are reluctant to talk about authors who inspired you. You said somewhere you started writing in around 1983. So that was two years after Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children came out. It would be easy to assume that as an inspiration like it was for a spate of new Subcontinental writers that followed Rushdie’s groundbreaking book?

MS: No! Actually, I will tell you why. I had no idea who Salman Rushdie was until 1989. I used to write but did little reading surprisingly! I was busy doing math. I didn’t have time to read for several years. In 1989 I was in France for seven months. There was this Spanish student there who said he had read this book in school, everyone had to read it. It was by an Indian writer. He than gave me a copy of Rushdie’s Shame [because] he could not find Midnight’s Children. [Shame] was the first literary novel I read. It was so bizarre and wonderful. So, that was my introduction to Rushdie.

HS: You went to the US in your early twenties. Was getting assimilated easy or difficult?

MS: Anyone who has education in one of these convent schools [in India] you kind of know what the US is going to look like. And it is truth in advertising because the US is exactly like it appears in [Hollywood] films, Mad magazine, and everything else [i.e. American cultural consumables].

HS: You think the US culture has lost some of its allure with globalisation?

MS: I think the US has squandered a bit of its international clout. I don’t know if it is economic or it is political. [But the US has made] bad political choices in the last 8 years. It is going to be interesting to see how that pans out. In terms of culture, there is always going to be a large segment of people both in the East and the West [who would look at the US for cultural consumption]. Even Europeans are very Americanised that way.

If it is to become less culturally attractive or become a beacon of culture, it is only because that culture has [already] spread across the world so much that it is almost like the US culture has won. It is the dominant globalised culture now, a lot of it. There was this article ‘The End of History’ by Fukuyama. It is not the end of history really but the end of culture. In some sense, the US has taken over and there is this globalised culture [extant around the world] with bits and pieces [of local and imported] much like the US potpourri, the melting pot.

HS: Do you get a feeling writing from the US that some things have irrevocably changed. You are no longer, what someone a decade ago would have called, a Third World Cosmopolitan, rather someone from a rising economic power in the world, and that it is the US that has increasingly become just another country?

MS: [Like in] India, people in the US need a lot of economic prodding before they will actually pay attention to any country. Finally, India has reached a point where yes they will have to pay attention now. And I suspect in the next few decades this Asian century that they talk about is really going to happen, there is no doubt in my mind.

HS: Do you feel anxious at times of being out of touch with the contemporary India, not being able to keep up with developments?

MS: A little bit, yes. As I said, I have been coming 3 times a year to India. So that has helped. But India is changing so fast that it is hard to keep pace now. And I haven’t ever worked in India, so if I am trying to depict what it means to work in India it is going to be a challenge. But then I knew very little about Indian history, I didn’t know anything about mythology when I started The Death of Vishnu. So, I can learn.

HS: You once rued being treated like an NRI. Has the reception in India improved since?

MS: Oh, it changed dramatically when The Death of Vishnu was released [in India]. I found that that is when I really came to India when especially the press here and the public, the audience that counted, embraced my book as an Indian novel. That was very energising. Since then, one of the nice things is that I have become an Indian citizen again because of the Overseas Citizenship of India which was always something that bothered me that I had to give it up. So it was very nice to be treated like, and be, an Indian again.

26 October 2007

A Question of Balance

Sir Mark Tully interviewed by Hemant Sareen on 7 July 2007. The interview appears in the New Delhi-based men's magazine. 'M', Sep-Oct 2007 issue.

Hemant Sareen: For many in India and in the West, you were the voice of a young nation going through one of the most tumultuous phase of its post-Independence history. Where did you get that sense of kinship with Indians and how did you come to share their anxiety, if at all, of how the world perceived them?

Mark Tully: I don’t know that I shared the anxiety, but I think one of the things that I had was that I was interested in this country. I had respect for the country. And, of course, I liked the country. And, I think those things are important. But at the same time, I had to say a lot of very unpleasant things sometimes about what was happening in the country. I had to be critical. But somehow I have found -- and I think the key to it lies with India and not with me -- that in India, provided people believe that you are genuine and you have a care and affection for them, they do not mind criticism. But they wouldn’t take it if you are always critical. So I think its part of how I managed to survive all these years.

But there were times when I was thrown out [of India] during the Emergency. And there were times when people were very, very critical indeed of us [the BBC]. And I wasn’t surprised because for instance if you have to report the first mutiny after the Operation Blue Star, and we were the people who first reported the mutiny, you are not going to be very popular with the army. But on the other hand it was my job to do that and in the end it was discovered that not only that mutiny, there were several other mutinies. If at the same time, you have to report something like the pulling down of the [Babri] mosque at Ayodhya, then the people at the spot are very angry about it. But it’s your job. You have to do these things. And it’s very important. I think the BBC would have lost its reputation if we had always been saying nice things about India. That’s not the way we went about things at all.

HS: Your ability to relate to India, did it have much to do with the fact that you were born in Calcutta?

MT: I think it does. I was born in Calcutta. My mama was born in what is now Bangladesh. My grandfather was born in Orissa. So, we were British in India from many generations going back. I had a great-great grandfather who was an opium agent in Ghazipur in the eastern Uttar Pradesh. So, we go back to five generations or so in this country. But as British: my childhood was very British, even when I was in India. I played with English, British boys. I only went to school with British children. That sort of thing. But, nevertheless, India is India and it rubs off on you whatever you are doing and with whoever. And when I came back here [later as a young man], I very quickly found that somehow my childhood came back to me and I felt at home here. So, I think it does in some way have something to do with that.

HS: What are your earliest memories of India?

MT: My earliest memories of India are of things like going for pony rides in Tollygunj in Calcutta. We used to go every Sunday for walks or bicycle rides to Behala [Calcutta] where there was an Oxford mission. My father was a great friend of the priest there. Also, of my nursery, I remember eating meals and saying how much I hated spinach. My nanny saying to me insistently -- I had an English nanny -- that I should never speak Hindi or Bengali. I remember some of the servants. I remember particularly one called Jafar who was a nursery boy. And there was another one called Abdul who was a khidmatgar -- my father had around 50 to 60 personal servants. So, I remember all that as well. Then I remember going to school on the Darjeeling railway and being very fond of railway. And I think, my love of railway started from that actually.

HS: You were very much a child of the Empire?

MT: Oh yes, very much the child of the Empire. Yes, I was a child of the Raj. You might even say, I am one of the relics of the Raj. [Laughs]

HS: Did you then get a sense of India, or what you later described as the ‘genius of Indian people to absorb and adopt,’ or even develop a basic understanding of the land and the people?

MT: No, no, not really. We were very much brought up to believe that India was India and we were British. So we didn’t learn much about India at all as children.

HS: When did you break away from that colonial mindset? Or if you like, when did you stop feeling like a sahib among natives?

MT: I don’t really think I felt like a sahib. I was too young. I never questioned it [the Empire]. I was only nine when I left [India]. I just thought this is the way things go, and I am English.

HS: What about later, when you returned to India as a grown up? Did you have Raj hangover?

MT: I was from a very young age a socialist. I became a socialist really because I could not understand how I could go to these very expensive schools in England and our village people [in India] went to very bad and poor schools. I had all these opportunities, and they didn’t have any. So, I became a socialist. Once you become a socialist you start to realise that privileged positions are very dangerous things. Then onwards, I thought to myself, well you know my position in India has been privileged. And that, I thought, was a dangerous thing. So, when I came back to India I knew that the last thing I wanted to do was to live the life of a sahib, or that kind of thing. Of course, I also knew that that sort of life had largely passed away. But I did know that I did not want to just live as an expatriate in this country. I was helped by the fact that from the first day I came here, I started to make friends because I worked for the BBC. People from All India Radio came to see me and helped me to establish myself, and became very good friends.

HS: You came to India via a very strange route. You went to Lincoln College in Cambridge to study theology in order to become a priest.

MT: But there is nothing contradictory between a priest and a socialist. My socialism was reinforced by my Christianity, because for me Christianity seem to be a religion which said you should care for the poor and be concerned about the poor and that sort of things.

HS: How big was religion when you were growing up in India?

MT: Well, it was very big really for me. The fact that I seriously tried to become a priest and I read theology at Cambridge, it was very big. But it was also very confusing. It was confusing because in Christianity we are very much concerned about sin. And I realised that I was a sinner in many different ways. I was a very wild young man. I used to drink a lot and I had lots of wild friends and things like that. And in some ways these contradictions [existed] between my Christianity and my wild part. But that didn’t mean Christianity was not a serious thing. It meant a failure of accommodation between [Christianity] and the way I lived my life.

HS: And as a child of the Raj, living in India, did you perhaps feel that in any way the Empire was about religion?

MT: In my family life, very much so. I think my first love for what I call Catholic ritual and church, the Church of England -- and we have quite a formal liturgical worship which I love still -- came I think from my going to Oxford missionary in Behala, especially to their Christmas eve services, I remember. So, from a young childhood I was brought up to go to church and I got to love the Catholic worship and, although I am Anglican Catholic not a Roman Catholic, the Anglo-Catholic worship from a very young age and that love has never left me.

HS: Most foreign correspondents are content writing descriptive books about their experiences in India. In your books, on the other hand, especially the latest, India’s Unending Journey, you exhort people to change, you want Indians to appreciate their past, you want the West to learn from India. You seem to have tremendous faith in people’s infinite capacity to change and self-reformation, kind of faith a priest would invest in his parish. There was something after all to your desire of becoming a priest?

MT: No, I don’t think so. My belief in the need for change being balanced by what I believe in, is not quite that everybody is easy to change, but life is all about accommodating change and not to be swept off your feet by it. What I think where my life was changed by India, is this belief that life is about balance and you never finally find the balance. Whereas in my English education, and through my Christianity in a way, I came to believe that life was about certainty. You found the way to live your life and that was it -- absolutely. And one went around in tramlines. Whereas India taught me that you never find a final destination. You will always be trying to find balance. And the important thing is to look out and see whether you are getting anything out of balance in your life, for instance, whether money has come to play play too big a role in your life, or search for fame is playing too big a role in your life. Other things can be, you know, the opposite. Whether you are so obsessed about not caring for money, that you become over-ascetic and you cannot look after people because you are not bothered about them at all. I also think that it is important in life to get the balance between free will and fate to acknowledge the fact that most of what has happened to you by free will, luck, or bad luck. And in this way, and at the same time, realising that you must too exercise your free will and that chances that you did, will be thrown away if you don’t exercise your free will. So getting the balance between the two. And this is important because otherwise for one reason you become arrogant. You think I have achieved all this, I am so clever, I am so great, I have so much charisma etc. etc. and you forget that the very simple fact that you were given a great gift when you were born. You didn’t choose to be born. You didn’t do anything to be born at all. And if you happen to be born with a very good brain, that’ not your achievement. It may have been an important achievement of your parents, but it is a gift given to you. And if you go around saying, ‘I am terribly clever,’ ‘I am very proud of myself because of my own achievements,’ then you get life out of balance. So that’s another balance, I think, that is very important.

HS: This is what you meant by ‘humility’ which you say India has taught you?

MT: Yes, India taught me humility. Humility of accepting your limitations, accepting that you cannot be certain about anything, accepting that you’ll never get anything totally right, you have to keep life in balance and accepting that you shouldn’t take things too far.

HS: This is part of your personal spirituality or morality, or your personal principles...

MT: Yes, you try to internalise it, certainly yes...

HS: But to expect a nation or a society to accept tenets of your personal spirituality or principles to consume mindfully in search of balance, isn’t that asking for too much? Isn’t that moralistic?

MT: No, I don't see it as being moralistic or in those terms at all. Just as I believe that in your personal life, if you do try to maintain a balance, if you do try to, you'll be a happier person. In the same way, I think, as a nation it is not a question of morality. It’s a question of common sense and being a happier nation. Just take one example -- consumerism. Consumerism is important to a certain extent. If we don’t consume, we will die. But on the other hand, if you take consumerism too far then you get charged up with greed. Because if you are not greedy beyond a certain extent, greedy for smart clothes, new cars, latest cars, all the time, the consumerist society, the consumerist economy, is trying to make us greedy. That sort of thing makes people very unhappy. Because greed is something that is never satisfied. So, what I am saying is that if you live in a consumerist society, if your nation or economy is built too much on on consumerism, if consumerism is off balance, then it’s not a question of morality, it’s a question of happiness. You will a lot of unhappy people.

HS: In India’s Unending Journey, you unapologetically quote someone who called you ‘an old-fashioned socialist and a romantic about India.’ Then, within the scope of ten lines you quote Spinoza, Manu, The Bhagwad Gita, and Rabbi Jonathan Sacks to denounce consumerism. But isn’t it too early in the day to speak of over-consumption to a section of Indian society embarking on its the first flush of consumption -- the first car, the first apartment, the first pair of decent shoes, necessities the West takes for granted?

MT: No, but I say in the book, correct me if I am wrong, that it is inevitable almost. I certainly point out that Indians were starved of consumer goods and I tell the story of how when I first came to India, diplomats sold secondhand lipsticks and things like that [to Indians]. So I certainly understand that it’s a bit like children in a chocolate shop at the moment. Suddenly they find this cornucopia, this array of goods and smart shops and all the rest of it -- people will get barmy. But I hope that the Indian tradition of balance will come in and balance will be restored. And I am not unduly pessimistic about [the ‘imbalance’ being left uncorrected by Indians].

HT: In the West, earlier associations with India, that had mostly to do with backwardness and poverty, are increasingly being replaced by those of technology and wealth. Did you anticipate in your long journalistic career in India the shape, manner, and the speed with which this new India emerged?

MT: Did I anticipate it would go up as quickly as this? No, to be honest, I didn’t. What I did anticipate was that I knew obviously the constraints on the Indian economy from the neta-babu raj, because I had written about it. and if you lifted those constraints, there would be an expansion. I knew Indians were very talented people. I didn’t foresee exactly which way it would go. I just didn’t believe that there would be such an expansion of economic activity because the whole thing had been suppressed in the neta-babu raj. And because when Indians went abroad, and I have written many times before about this anomaly, they did fantastically well [there]. But when they came back they couldn’t do anywhere nearly as well because of the whole license-permit raj was on their head.

So obviously I didn’t foresee necessarily that it would be so much in the IT sector, and I never foresaw that manufacturing would grow as it has done. So details, no, I didn’t. But in principle I thought there would be quite a rapid expansion of the economy [if the ‘constraints’ were removed].

HS: One of your pet themes and concerns, about which you have often written and spoken, is that one should build on what one already has. In No Full Stops In India (1991) you rued the fact that Indians don’t value their past and ‘the genius of Indian civilisation.’ Even in your public disagreement with the Director General of BBC, John Birt, which led to your resigning from the BBC in 1997, you were highly critical of the way he discarded a whole tradition, that had made BBC a well respected organisation around the world, in the name of restructuring. Does it surprise or disappoint you that India has not built on what it already had and that what it has become is not based on its own but borrowed beliefs?

MT: No, you see, since I wrote that, I have always feared that India will think that the way things are done in the West, is a model for the whole world, and this is the way India should do it. I have always profoundly believed that that is not so. You know you look at the record of other countries who have developed in quite different ways, Japan is the obvious example, to the way that the West developed. Even in the West, you get what we call the American-British [capitalist] model, the Scandinavian [welfare state] model, and the German model coming in the middle of the two. And I am afraid to say that I find the American model and my own country’s [British] model the least attractive. But I believe very strongly that there is a great strength in India’s culture and it is this strength on which India should build. One of these things which distresses me in the so many of the BBC-arguements was the destruction of the past. The idea that in the organisation for which people like me had worked for over thirty years that we knew was highly regarded, not because of us but because of the organisation it was, around the world, this man [John Birt] came along and said it was all rubbish and needs to be pulled down. I think another balance which is absolutely essential in national life, and indeed in personal life, is the balance between tradition and change. You can have too much tradition, as perhaps India does, or you can have change which is too destructive, throwing-the-baby-out-with-the-bathwater kind of change.

HS: “Western thinking is distorting and still distorts Indian life” you wrote in 1991. Does Western thinking still distorts Indian life? And is it due to the inability of India to interpret the West coherently? Or is it the fault of the western thinking itself?

MT: You can see it in two ways. I said before that I don't believe that what happens in one culture necessarily to be exactly imitated in another culture. India has a different culture. India has different problems as well. India is a very diverse country in every sense of the word. I personally feel, as I have written in India’s Unending Journey, we in the West have got things wrong and gone off balance. I don’t want that imbalance coming into India. But you know what’s happening in India is that all the pressures are coming on her to do what big business and western diplomats tell her to do. Everyone is telling her if you don’t follow this way, you won’t be able compete globally, and all the rest of it. And I don’t want India to blindly follow their way. I think, actually, gradually in the West, in Britain for instance, people are realising that the balance has gone too far, that they need to get more into the middle of the road.

HS: It seems, in India development happened not because of the government, but despite it. Just like the IT industry flourished because the government had no clue what it was all about and hence could not regulate it. Reforms too are more about the government stepping aside, withdrawing. The development in India so far is popular -- a section of the society, freed from state’s clutches, finds solutions to problems the state had failed to provide.

MT: You are absolutely right, but you have to be careful. Because the government interfered too much at one stage, then inevitably people started to think this was the whole problem and therefore said, ‘Let’s go completely the other way. We don’t want the government to interfere in everything’. In my view, the government does need at times to direct the economy, and to provide certain services still for the moment. Otherwise a whole lot of people are going to be left out. They have these super-speciality hospitals coming up [in India], what good are they for someone who earns one thousand rupees a month -- he wouldn’t get through the doors of a place like that. So, it comes back to the need to have a balance. Yes, the government does have a role to play, but, this is a hugely important thing, a hugely important thing, the government itself needs to have a really complete overhaul because there is no point in the government interfering if the government itself is corrupt, represents vested interests, and is taking decisions not because it genuinely believes in securing the interests of the largest number of people of the country, but because it serves certain vested interests. So good governance and fair governance is something which is severely lacking in this country. Therefore you cannot have a decent balance between government interference and the liberation of talents through giving people greater and greater freedom. This is a balance you need to get: the balance of the socialist way, the idea of directing the economy, and the capitalist idea of freedom of enterprise and the expression of individual talent. You are not going to get this balance right if you have bad governance. And you do have bad governance, I have no hesitation in saying that.

HS: You don’t think trickle-down economics works? Having seen Indira Gandhi’s pathetic attempts at garibi hatao and a planned economy’s limits, you seem to be advocating policies that suggest a nostalgia for that very same pre-liberalisation socialism.

MT: No, even in the book [India’s Unending Journey] I have been extremely critical of that. I do not think that was a better way at all. It was not a better way for one very obvious reason, as I have already said -- bad governance. What’s the point of nationalising institutions if you are not able to run them properly and well, and fairly. Look at all the corruption that came in the banking system, a decision [i.e. to nationalise banks] which was meant to create more equitable distribution of credit, didn’t do so because of corruption. No, I don’t think that was right. I think also, it was predicated on giving the government far too much say. It was unbalanced in the other way.

HS: Even if the public sector and the nationalised institutions had been well-run, do you think socialism would have worked for India, it hasn’t done much good elsewhere?